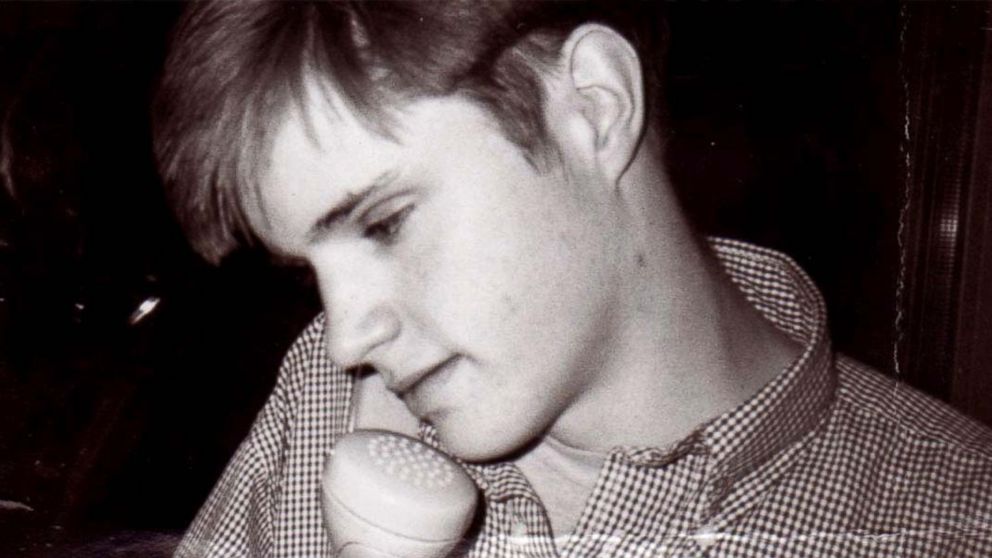

Twenty years ago, Matthew Shepard was a “smart, funny” 21-year-old, no different than any other young man that age.

He was an “ordinary kid who wanted to make the world a better place,” his parents remembered.

But in October 1998, that all changed, when the openly gay college student was abducted, beaten and tied to a fence in Wyoming.

His life ended a few days later, and with it came a widespread awareness of the dangers that members of the LGBTQ community face every day. The homophobic brutal killing also served as a catalyst for progress in America’s laws and culture.

In the two decades that have passed, however, it remains debatable how far the country has come since the shock of that crime.

Shepard, a student at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, spent Oct. 6, 1998, at a meeting of the school’s LGBTQ student group planning upcoming events for LGBTQ awareness week, Jason Marsden, executive director of the Matthew Shepard Foundation, told ABC News.

He then grabbed coffee with friends before heading to a bar in Laramie in southeastern Wyoming.

Shepard was sitting alone at the bar, drinking a beer, when he was approached by Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson. They later confessed they had “developed a rouse in which they’d pretend to be gay to win Matt’s confidence,” Marsden said.

“They could offer him a ride home and rob him,” he added.

McKinney and Henderson kidnapped Shepard and told him he was being robbed, Marsden said.

They “started physically assaulting him, first with fists and then with a .357 magnum pistol that Aaron McKinney was carrying,” Marsden said.

McKinney and Henderson took Shepard to a prairie east of town, where they tied him to a fence, Marsden said.

McKinney hit Shepard about 20 times in the head and face with the end of the pistol, Marsden said, before the two stole Shepard’s shoes, got in their truck and drove back to town.

Shepard was found the next day, 18 hours later, by a passing cyclist. He was taken to a Laramie hospital but his head injuries were so severe that he needed a neurosurgeon, so he was moved to a Colorado hospital, Marsden said.

Shepard’s parents at the time were in Saudi Arabia, where his father worked. They flew back and were with their son at the hospital for his final few days, Marsden said.

When his mother, Judy Shepard, saw the badly beaten college student in the hospital, “he was all bandaged, face swollen, stitches everywhere,” she told ABC News’ “Nightline.” “His fingers curled, toes curled, one eye was a little bit open.”

Shepard died on Oct. 12.

The loss “never heals,” his father, Dennis Shepard, told “Nightline.” “He was just an ordinary kid who wanted to make the world a better place. And they took that away from him. And from us.”

Matthew Shepard was a mischievous, stubborn and argumentative child, his father said.

He grew up to become very interested in international human rights, particularly women’s rights in the Middle East and Asia, and he studied political science, said Marsden.

“His goal was to work for the State Department to try to bring the same privileges and rights he thought he had in America to other countries,” Dennis Shepard said.

A few years before his death, Matthew Shepard came out to his mother on the phone.

“He said, ‘Mom I’m gay.’ And I said, ‘What took you so long to tell me?'” she recalled. “Rejection was not ever an issue in our family.”

Their son was then living an openly out life.

“Everybody he met, he said, ‘Just to let you know ahead of time, I’m gay,'” Dennis Shepard said.

“It was like, ‘This is who I am, and that’s the way it’s going to be,'” added Judy Shepard.

Dennis Shepard wasn’t worried about his son’s safety.

“We didn’t realize the amount of violence and discrimination … against the gay community until after he died,” he said. “We thought, he was born here … he has all the rights, responsibilities, duties and privileges of every other American citizen.”

The shocking homophobic crime in the sparsely-populated state garnered national sympathy. The outpouring of love was immediate as flowers and stuffed animals filled the hospital.

“This is before the term viral existed, but it really did go viral,” Marsden said.

“It spawned candlelight vigils all over the country. There was a mass protest on Fifth Avenue in New York in which almost 100 people were arrested,” Marsden said, as well as a vigil at the U.S. Capitol with celebrities and members of Congress.

“All of these spontaneous vigils were organized by volunteers independently of one another. All of the calls to action for hate crime legislation were the work of individual civic and political leaders,” Marsden explained. “It was a spontaneous outrage about the severity of this crime and the overall phenomenon of hate crimes against LGBT people, which were starting to get more social attention around this time than they had received in previous years.”

But it wasn’t all sympathy.

Members of the Westboro Baptist Church protested the funeral, picketing with anti-gay signs.

Rev. Fred Phelps and his parishioners traveled from Kansas to Laramie for the funeral and trial, protesting with brightly colored signs and spewing hatred.

Friends of the slain student dressed in angel costumes and staged a counter-protest encircling the parishioners so their signs wouldn’t be visible.

After McKinney and Henderson were arrested, Henderson waived his pre-trial investigation and took a plea agreement, agreeing to two life sentences.

McKinney went to trial, and defense attorneys argued his violent actions were “gay panic” — a reaction to Shepard making a sexual advance.

“When the defense gets out there and starts talking out of, the victim’s fault, you know, ‘gay panic,’ … you just really want to scream,” Judy Shepard said. “One of the portions of his statement was that Matt was coming onto him … if that’s your defense, then every woman in a bar who gets hit on, she has the right to murder the guy sitting on her? That’s just absurd.”

The “gay panic” defense is still legal in most states but has been outlawed in a few. It’s been used since the 1960s in more than half of the states in the country, according to the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law.

McKinney was convicted on numerous kidnapping and murder charges. Before sentencing, his attorneys, the Shepards and the prosecutors agreed to two consecutive life sentences in exchange for taking the death penalty off the table.

McKinney has declined to speak to ABC News while Henderson did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Shepard’s murder shined a light on the scope of federal hate crime laws, which at the time did not include sexual orientation or gender identity.

“Matt’s murder immediately raised the visibility of that effort and, although it took until 2009, it did eventually pass and was signed into law by President Obama,” Marsden said.

The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act added crimes motivated by the victim’s gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and disability to the federal hate crime law.

James Byrd Jr., who was black, was murdered by three white supremacists in Texas in June 1998. Byrd was dragged behind a pickup truck, decapitated and dismembered.

The moment Obama signed the hate crimes law “was amazing,” Judy Shepard said. “He understood social injustice. And to be there with James Byrd’s sisters when they, when he actually signed, signed into law, it was an incredible experience. And it was a relief and it was also a total understanding that there was just really a lot more left to do.”

“There’s now been dozens of cases prosecuted against violent offenders who attack people based on their sexual orientation or gender identity or other characteristics that are now easier to prosecute than they were under the previous law,” said Marsden. “Also several states either passed hate crime legislation for the first time or made their hate crime laws tougher.”

Beyond the federal hate crime law, in the years since Matthew Shepard’s death, among the most substantive legislative wins for the LGBTQ community were the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell in 2010, so gay military members can serve openly without fear of being dismissed, and the legalization of same-sex marriage across the country in 2015.

The tragic murder also led to the creation of the Matthew Shepard Foundation, the mission of which “is replacing hate with compassion, understanding and acceptance,” Judy Shepard said.

“The core of what we do is trying to get individual people excited about making a difference,” Marsden said of the foundation. “If millions of people wanted to act in tandem, we could make hate obsolete. We could define our social norms in such a way that this kind of behavior would start to go away.”

For Judy Shepard, one of the best signs of cultural progress is seeing Gay Straight Alliance groups ramping up in schools. In Wyoming, where there’s a population of just 500,000, she said there are 19 Gay Straight Alliances.

Matthew Shepard’s story has also lived on through various creative works, including the “The Laramie Project” and “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” plays, which tell the story of how Laramie residents reacted to the murder.

They are among the most performed plays in American high schools, Marsden said, and have even been performed across the world in different languages, Judy Shepard said.

“It’s a universal story,” she said. “If you remove the sexuality from the story and insert race or religion, it’s exactly the same story of intolerance in a community or intolerance of individuals and how it affects a community.”

“Matt’s story, I think, was inspirational to many people, especially people his age who had not previously been active in LGBT rights who started doing so. Some have gone on to be really prominent activists in the community,” Marsden said.

“I thought we were making such great progress in the Obama administration,” Judy Shepard said, but after the 2016 presidential election, she felt the progress of the foundation was at “ground zero again.”

The Trump administration has brought changes including an order to ban transgender troops in the military and a new “religious liberty task force” that advocates fear will provide an excuse for discrimination.

Just this week, a new policy went into effect in which the Trump administration will no longer provide visas for same-sex domestic partners of foreign diplomats and U.N. officials serving in the U.S.

“I’m just so mad that we are regressing,” Judy Shepard said. “We’re back on the road talking about hate and acceptance and loving your neighbor and, you know, all those things again.”

During the Obama administration, the Department of Justice “was working with us.”

“They would set up conferences to educate law enforcement, NGOs and nonprofits on how to deal with hate crimes. How to address them, how to identify them, how to work with victims. And they would invite us to come,” Judy Shepard said. “We visited several countries, 25 countries with [the] State Department. Now we’re not.”

“Now the [Department of Justice] definitely does not want to work with us,” she continued. “Civil rights is not an issue, a primary issue, for the DOJ anymore. … So we don’t get calls from them anymore.”

To Marsden, the degrees of progress for LGBTQ rights in the past 20 years vary.

Especially in urban areas, Marsden said he thinks “LGBT people have a good deal more personal freedom, career opportunities, are much less subject to discrimination. I think a lot of our schools are safer, including bullying issues, which of course affect people way beyond the LGBT community — they affect anyone who is different in some way or another than the perceived norm.

“However, if you look back in history every time there’s great progress there’s also a great backlash going on,” he said, citing how the end of slavery prompted the evolution of KKK and Jim Crow, while the 1960s Civil Rights movement ignited racial violence.

“All of the advances we’ve made have been great but they haven’t reached everyone. It’s still a very hard time to be a [transgender] kid in America even in more enlightened parts of the country, certainly in more rural parts of the country.”

A Gallup poll from May 2018 found that 31 percent of people don’t think marriages between same-sex couples should be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriages.

“The overall lesson about looking back on progress is you have to fight to keep it. It can be very easy politically in this time in America to reverse the accomplishments made in the last 10 or 15 years,” Marsden said.

“I want people to be very conscious of their safety,” said Judy Shepard, warning that hate is still very much out there and that women, people and members of the LGBT community are especially vulnerable. “Especially now, when we hear so much vitriol being shouted from our leaders.”

“The number of hate crimes against LGBT people has gone up in the last two years, just like racial and religious hate crimes have,” Marsden said.

Reported hate crimes in the nation’s 10 biggest cities rose 12.5 percent last year — the fourth consecutive annual rise in a row and the highest total in over 10 years, according to an analysis from California State University San Bernardino’s Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism.

“Most hate crimes and discrimination are racial or religious — LGBT is a smaller percentage,” Marsden said. “We see, sadly, the kind of person who hates a certain race it’s pretty likely you’re the kind of person that hates a certain religion or a certain sexual orientation or gender identity, as well.”

To the slain student’s mother, Matthew Shepard shouldn’t just be remembered for his legacy — he should be remembered for his life.

“I want people to remember that he was a person, that he was more than this icon in the photograph and the stories,” Judy Shepard said. “He was just, he was a 21-year-old college student who drank too much, who smoked too much and didn’t go to class enough. Just like every other 21-year-old college student. He had flaws. He was smart, funny. People just were drawn to him. And there was a great loss not just to us, but to all his friends. And people who hadn’t met him yet.”

ABC News’ Meghan Keneally and Conor Finnegan contributed to this report.