After last year’s deadly clash between white nationalists and counter-protesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, the federal government quietly spent millions of dollars to hire private security guards to stand watch over at least eight Confederate cemeteries, documents from the Department of Veterans Affairs show.

The security effort, which runs around the clock at all but one of those VA-operated cemeteries, was aimed at preventing the kind of damage that befell Confederate memorials across the U.S. in the aftermath of the Charlottesville violence.

None of the guarded cemeteries has been vandalized since the security was put in place. Records obtained by The Associated Press through the Freedom of Information Act show that the VA has spent nearly $3 million on the cemetery security since August 2017. Another $1.6 million is budgeted for fiscal 2019 to pay for security at all Confederate monuments, which could include other sites. The agency has not determined when the security will cease.

Private security was needed “to ensure the safety of staff, property and visitors paying respect to those interred,” Jessica Schiefer, spokeswoman for the VA’s National Cemetery Administration, said in a statement. The agency “has a responsibility to protect the federal property it administers and will continue to monitor and assess the need for enhanced security going forward.”

Most of the protected cemeteries are in the North, in places far removed from the Confederacy. Vast numbers of the buried soldiers were prisoners of war who were held nearby. Many succumbed to smallpox and other diseases. The cemetery monuments are typically simple and solemn, serving more to acknowledge the deceased than to celebrate the slaveholding nation they defended.

Government watchdog groups and some members of Congress question if the spending is still necessary. Steve Ellis, executive vice president of the non-partisan Taxpayers for Common Sense, said the cost of security represents the sort of “spending inertia” too common in government.

“Unfortunately what happens with the government is once you start spending money on something, you generally continue to spend money on it,” Ellis said.

Democratic Rep. Bobby Rush of Chicago, whose district includes one of the protected cemeteries, said in a statement that while he supports the VA’s decision to prevent vandalism, officials “must remain vigilant in evaluating” government spending.

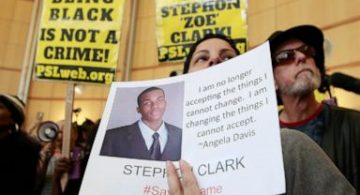

Monuments to the Confederacy have become especially polarizing since nine black parishioners were gunned down by an avowed white supremacist at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. The confrontation in Charlottesville on Aug. 11, 2017, reopened the wound. In the weeks that followed, vandals damaged Confederate sites across the country, and cemeteries were not spared.

A bronze statue of a rebel soldier was toppled and decapitated on Aug. 22, 2017, at Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio. Two days later, the VA contracted with the Westmoreland Protection Agency, based in Sunrise, Florida, to provide unarmed security guards at Camp Chase and two other cemeteries — North Alton Confederate Cemetery in Alton, Illinois, and Woodlawn National Cemetery in Elmira, New York. The 30-day contract cost $91,357, according to the documents.

About a week later, someone threw paint on a 117-year-old Confederate memorial at Springfield National Cemetery in Missouri, hours before President Donald Trump was scheduled to speak in Springfield.

On Sept. 6, 2017, the VA amended the monthly contract to add Springfield and four additional national Confederate cemeteries: Point Lookout Confederate Cemetery in Scotland, Maryland; Finn’s Point National Cemetery in Pennsville Township, New Jersey; Confederate Stockade Cemetery in Sandusky, Ohio; and Confederate Mound at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

Schiefer did not directly answer questions about why the eight cemeteries were chosen but said the National Cemetery Administration “routinely monitors the need for additional protection and security at all of its sites.” Decisions, she said, are based on factors such as historical significance, replacement and repair value, and previous vandalism or threats of vandalism at particular sites.

The monthly contract for all eight was renewed in September 2017. All told, the VA spent about $462,500 on security through Oct. 23, 2017, when it agreed to an annual contract with Westmoreland at a cost of just under $2.3 million. Westmoreland hired The Whitestone Group, based in Columbus, Ohio, as a subcontractor.

The funding came from the VA’s budget and did not require an emergency appropriation, Schiefer said.

Contract specifications call for round-the-clock security at seven of the cemeteries, and during daytime hours only at the Chicago cemetery. Spot checks by the AP found guards at the cemeteries in Columbus and Alton, but no one during the day at the Chicago cemetery. Schiefer said the VA does not discuss security procedures.

At the Alton cemetery, a lone guard watched over the grounds from his truck. The guard, who works for the Whitestone Group, declined an interview request and would not give his name.

The cemetery, near St. Louis, consists mostly of grass and a few stately trees over rolling hills. Its main feature is a 58-foot-tall granite obelisk with plaques naming the 1,354 Confederate dead buried there, including many who died of smallpox while prisoners of war.

Jeff LaRe, executive vice president of The Whitestone Group, said an uptick in vandalism of Confederate monuments this past summer was evidence that cemetery security remains necessary. Protesters in August toppled a century-old statue at the University of North Carolina, and vandals put paint on statues in Salisbury, North Carolina, and Richmond, Virginia.

Darrell Maples, a Missouri-based commander for the Sons of Confederate Veterans, agreed.

“I don’t think it’s going to go away anytime soon,” Maples said.

Whether because of the added security or other reasons, no vandalism has occurred at any of the cemeteries since the August 2017 incident in Springfield, the VA said.

Protesters gathered at Confederate Mound in Chicago in April, at the same time the Sons of Confederate Veterans rallied there. But amid a heavy police presence, nothing was damaged. Schiefer said that twice in September 2017, suspicious vehicles were spotted near the statue at the Elmira cemetery but drove away when the guard approached.

Curtis Kalin, spokesman for the government watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste, said the additional security was understandable after the rash of vandalism in 2017.

“However, when the threats and vandalism have all but ceased, it might be time to rethink” the spending, Kalin said in a statement.

———

Associated Press photographer/videographer Jeff Roberson in Alton, Illinois; writer Andrew Welsh-Huggins in Columbus, Ohio; video journalist Teresa Crawford in Chicago; researcher Jennifer Farrar in New York; and former Jefferson City, Missouri, writer Blake Nelson contributed to this report.