A California man was freed from prison after serving 23 years of his life sentence on a joyriding conviction, including eight years in solitary confinement for possessing a book written by the co-founder of a notorious prison gang.

His attorneys say it’s unconscionable that he was set to die in prison for nonviolent crimes.

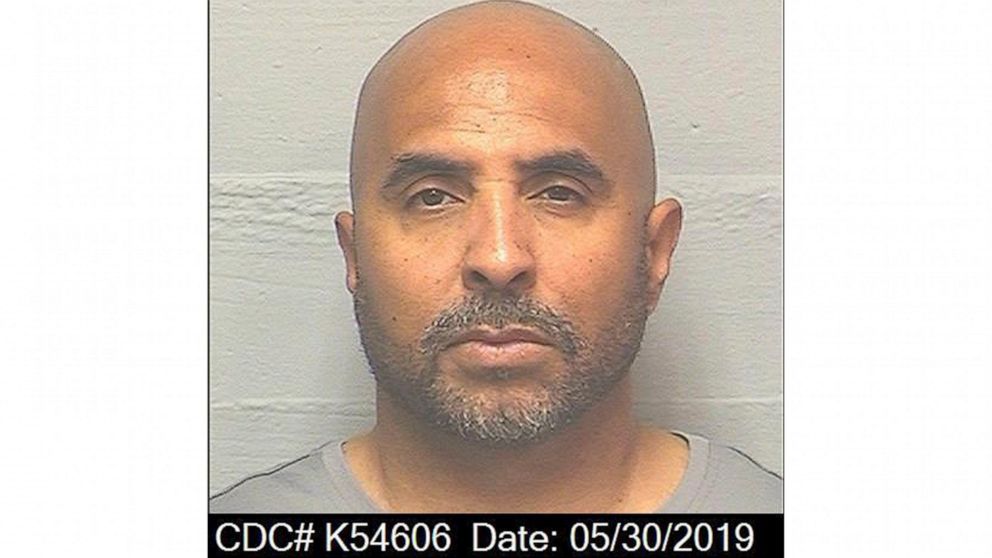

Kenneth Oliver, now 52, was given the life sentence at 29 under California’s strict “three strikes” sentencing law for repeat felons.

Voters eased the law in 2012 to allow life sentences only when the third strike is for a serious or violent felony.

But Oliver was ineligible for a new sentence because he was found with purported gang materials including a book called “Blood In My Eye,” completed by Black Guerilla Family co-founder George Jackson days before he died during a bloody attempt to escape from San Quentin State Prison in 1971.

Oliver was freed Monday after Los Angeles County prosecutors dropped their objections “in the interest of justice,” and after the state corrections department expunged his gang-affiliation record and paid him a $125,000 settlement for his time in solitary.

“It’s almost impossible to believe that what happened to Ken happened here in California. You know, people think of this as an enlightened state and both the sentence and the time in (solitary confinement) don’t square with that,” said Ward Johnson, lead counsel on the case at the Mayer Brown law firm.

Oliver was arrested while a passenger in a stolen vehicle and pleaded guilty to taking a vehicle without permission. A stolen handgun was later found in his hotel room, prosecutors said. It was the latest in a string of crimes dating to an armed robbery when he was 16.

Los Angeles County prosecutor Nicol Walgren said she was impressed by Oliver’s rehabilitation in prison and preparation for a successful life outside. She called him the kind of prisoner that voters envisioned when they eased the three strikes law.

“Ken’s sentence of 50 (years)-to-life was much longer than (for) rapists and murderers,” said Michael Romano, director and founder of the Three Strikes and Justice Advocacy Projects at Stanford Law School. “There should be some proportionality.”

Voters agreed when they opted to free nearly 3,000 third-strike inmates, Romano said. Yet he estimated that another 200 to 500 qualifying inmates remain incarcerated largely because they can’t afford the legal team that worked for free on Oliver’s behalf.

“I really haven’t wrapped my head around it fully,” Oliver said 24 hours after his release and after he and his father, a university dean in Georgia, celebrated with dinner at the Cheesecake Factory. “I do feel like time has passed me by but I’m trying not to be negative about it.”

He’s now in a transitional housing program and plans to become a paralegal, helping others through social justice programs while reconnecting with his three adult children.

He couldn’t understand being sent to solitary confinement for possessing a book readily available in most campus libraries, but spent his time studying the law and filing the federal lawsuit that eventually helped lead to his release.

“You’re single-celled for most of the time and every time you leave the cell or are escorted out you have to strip naked and bend over and cough,” Oliver said of his time in solitary. Exercise was three hours a day in a six-by-nine foot “dog kennel.”

“Some people go crazy in there,” he said. “Me, I chose to read and try to find a way out of there and not let that circumstance define me.”