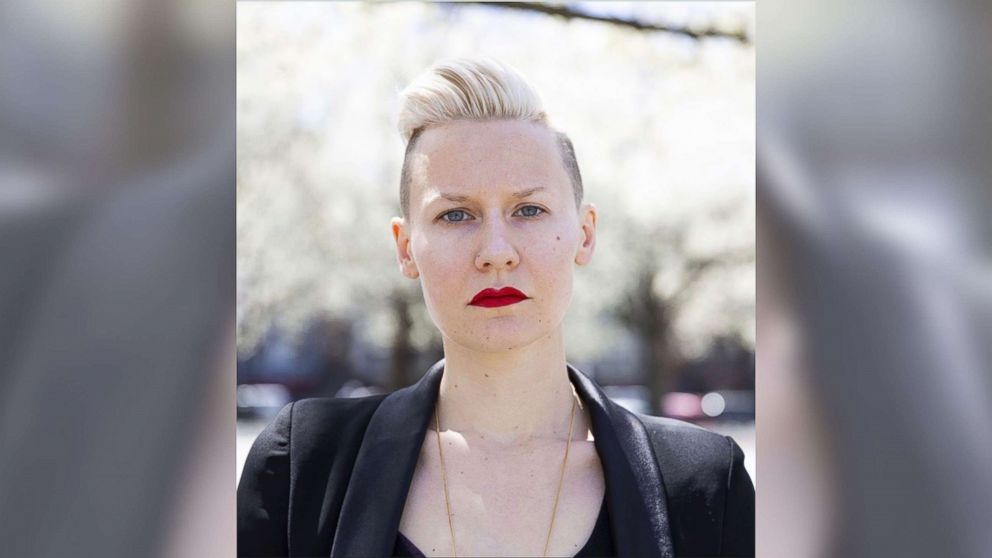

Alison Turkos was 16 when she said she was raped at a friend’s graduation party. A 19-year-old man entered the room where she was sleeping, got on top of her and put his hand over her mouth. It was her first sexual experience. When she came downstairs the next morning, “everyone in the kitchen clapped as if to indicate that was a really great thing.” When her dad came to pick her up from the party, she said nothing.

“I got in the car and the minute that I closed that car door, I remember thinking to myself: I will never tell a f—— soul about this. I felt so dirty, I felt so disgusting, I felt like it was my fault,” Turkos told ABC News. “At the time, I didn’t have the language around rape and consent. I didn’t have the knowledge around anything like that. I didn’t know.”

Turkos would continue to stay silent for more than a decade, including after a second rape when she was 18 during the first week of her freshman year of college.

“I never told my parents until this year. I’m 30 now. I never told them what happened in high school and what happened in college,” Turkos said.

She added, “I wanted to be put together, I wanted to make my parents proud, and being a victim of a violent crime, of two brutal rapes, was not something that I thought fit into that perfect box.”

She said she can relate to Christine Blasey Ford, the woman who has accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault in high school, because of her own experiences and decision not to report the assault to her parents or others.

This week has been hard for Turkos and many other survivors of sexual assault. The president has publicly weighed in on the sexual assault allegations against Kavanaugh, slamming the women who have come forward to accuse him and saying Kavanaugh is “an absolute gem.” Kavanaugh himself has flatly denied all of the allegations, deriding them as “smears.”

Senators will soon weigh in on whether the women who have accused Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct should be believed. Many survivors hear echoes of their own fears about what would happen if they reported.

“For those of us who have experienced this first-hand, and our bodies have literally been crime scenes, the news cycle is daunting and it is horrific,” Turkos said. “It can be inescapable. It’s impossible and it feels like I’m sometimes drowning in it and I can’t escape it because I’ve lived through this three times.”

Across the country, group texts between survivors have lit up with self-care memes from Instagram. Stories of why #WhyIDidntReport have flooded Twitter timelines. Many, like Turkos, have come forward to share their stories, some for the first time.

But other survivors are choosing to keep quiet. They say the attitude surrounding survivors hasn’t changed with the times: you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t.

Beverly Engel is a psychotherapist and author of more than 20 self-help books, including a forthcoming book on surviving sexual assault. She said shame and self-blame are central reasons why survivors of assault don’t report these crimes.

“Victims are often too ashamed to come forward. Sexual assault is a very humiliating and dehumanizing act against someone. The person really feels invaded and defiled, and there is a lot of shame attached to that,” Engel told ABC News.

She continued, “Attached to that shame is a lot of self-blame. Victims of sexual assault almost always blame themselves, and we can understand why, because in our culture, we tend to blame victims in general. We say things like, ‘She shouldn’t have been wearing that kind of outfit, she shouldn’t have drank so much, why did she go to that party?’ We find some reason to blame the victim.”

Those narratives, especially whether a woman had been drinking or not, have been at play in the discussions of the women who have accused Kavanaugh, Engel said. In addition to shame and self-blame, many survivors don’t report because they fear retaliation or worry that they will not be believed.

One out of every six women in the U.S. and one out of every 33 men has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime, according to an analysis of 2010 to 2014 Bureau of Justice Statistics by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization.

Turkos said she did not report the two rapes she endured at 16 and 18. But she decided to go to police when she was assaulted for the third time. Turkos said she was raped by attackers she didn’t know after being picked up in a car in Brooklyn, New York, on Oct. 14, 2017. She reported the assault 60 hours later, even submitting to a sexual assault forensic exam kit at the hospital. She said she was asked to give six uniformed officers a statement about the attack.

She alleges a detective asked her friend to take photos of her bruised body in an employee bathroom at the police station, “which was traumatic for me and traumatic for her.” The New York Police Department confirmed the date of the incident but declined to comment on her case for this story.

Rather than helping her feel safe, Turkos said, the reporting process was traumatic.

“I am a victim who is in this space of, I didn’t report my first two rapes and I did report my third rape, and so I sort of understand the world from both sides,” Turkos said. “Even when I did report and ‘did the right thing,’ my reporting process was horrific and traumatic and terrible. So I’m thinking about that a lot when I’m seeing all these people, and people in positions of power and elected officials, who are telling us: ‘Why did you do this? Why didn’t you do that?'”

Turkos is far from alone. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, only 23 percent of victims of rape or sexual assault reported those incidents to police in 2016, compared to 54 percent of robbery victims and 58 percent of aggravated assault victims. There are a number of reasons why people who have experienced sexual abuse are less likely to come forward than victims of other crimes, according to Keeli Sorensen, vice president of victim services RAINN.

“There is a wide array of reasons that people don’t come forward, and from our perspective, all of them are legitimate. It really depends on the person and the way that they view what’s necessary for their healing out of the situation,” Sorensen told ABC News.

“If I am someone who believes there is going to be retaliation, or the person who committed and perpetrated the events against me is well-respected, has a high-profile within a community, a community I care about, I am going to see a lot of risk related to reporting, particularly because it will instigate an investigation, and that might be a risk I’m not willing to take,” she added.

Even if survivors choose to report sexual assaults, justice is not always served. Out of every 1,000 rapes, 994 perpetrators will walk free, according to a report by RAINN that cited 2010-2014 Bureau of Justice statistics. That means perpetrators of sexual violence are less likely to go to jail or prison than other criminals, according to RAINN. Meanwhile, the emotional, physical or psychological risks of reporting an assault might be very high.

“Of course, there are a lot of responsible and well-trained law enforcement that range from the various federal departments to local departments. But their role is to identify a violation of the law and bring perpetrators to justice. Their role is not to facilitate the continued well-being of the victim’s experience. That is something that there is specialized training to do and people have, thank goodness, prioritized, but we can’t guarantee that because that’s not how the system is built,” Sorensen said.

Turkos can’t say whether she regrets reporting the October 2017 assault because in the moment, it felt right to do so. No one has been arrested in the incident, even though reporting it upended her life.

“I think because the one-year anniversary is swiftly approaching, it’s really sitting heavy for me,” Turkos said. “It has been a year and I’m still waiting and my perpetrators are still out there. And one of the things I keep saying is I didn’t report at 16, I didn’t report at 18, and my perpetrators are still out living their best lives in the world. I reported at 29 and my perpetrators are still out there living their best lives in the world. And I have to attempt to get through every single day. I have severe PTSD and severe anxiety.”

To work through the emotional, psychological and physical impact of assaults, survivors often band together for support. Sometimes it takes a critical mass of people — as in the case of the #MeToo movement — to come forward and encourage others to speak out.

Survivors of sexual assault spoke out after Trump questioned in a tweet why Ford had not reported the alleged assault by Kavanaugh.

“I have no doubt that, if the attack on Dr. Ford was as bad as she says, charges would have been immediately filed with local Law Enforcement Authorities by either her or her loving parents. I ask that she bring those filings forward so that we can learn date, time, and place!” Trump wrote.

In response, actress and #MeToo movement activist Alyssa Milano tweeted back.

“Hey, @realDonaldTrump, Listen the f— up,” Milano wrote on Friday. “I was sexually assaulted twice. Once when I was a teenager. I never filed a police report and it took me 30 years to tell me parents. If any survivor of sexual assault would like to add to this please do so in the replies. #MeToo.”

The hashtag #WhyIDidntReport has now been tweeted more than 800,000 times according to Spredfast, a tweet-tracking site, with public figures and private people alike sharing their stories, including Turkos.

The #MeToo movement, among others, has done a lot to open up conversations about sexual assault but negative media coverage of survivors can have the opposite effect, too. According to RAINN’s analysis of Bureau of Justice Department Statistics, from 2005 to 2010, 20 percent of victims who said they did not report their assaults did so because they feared retaliation.

Survivors and advocates are worried that the negative coverage of the women who have accused Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct could have that effect. For example, Ford has said she has received death threats since coming forward and all of the women have had their credibility questioned.

“It’s our greatest fear that this is the response for a victim or survivor. Because it not only completely shuts down their experience, it makes them feel as if it didn’t happen. They do not have the right to their own story and it shuts down the experiences of people who have had these kinds of perpetrations acted upon them as well,” Sorensen said.

Often, survivors are not only blamed for the circumstances that led to the assault (such as what they were wearing, or whether they had been drinking), but also criticized in how they did or did not “fight back,” a reality that can be particularly brutal for male victims of assault who are told they should have been able to overpower their attacker, Engel said.

In fact, the body has a self-defense mechanism called “tonic immobility” that causes temporary paralysis in some people during an assault, Engel said.

“It’s like a deer-in-the-headlights reaction where the body just completely freezes and it becomes very still and rigid and you become very silent,” Engel said. “Animals that are really overpowered freeze and it’s that reaction that’s a very powerful survival mechanism. Rapists are about power and control and once they feel they have power and control over their victims, they have gotten what they wanted. If a person tries to fight them, they might get more aggressive. So every person has to decide for themselves what works best in that situation.”

Engel said in other situations, people choose to fight back, but ultimately, believing that there is only one right way to report and recover from an assault hurts survivors.

“We are so often blamed: ‘Why didn’t you come forward? Why didn’t you tell someone? Why did you tell someone but not in this way?'” Turkos said. “It makes us fall back into this ‘perfect victim’ narrative: this is how a rape victim should look like, this is how they should act, this is how they should behave, this is how they should report.”

Only when that narrative is dismantled can the conversation around sexual violence really move forward, she added. To that end, Turkos wrote a letter last week to senators in support of Ford. It has been signed by hundreds of sexual assault survivors.

“There is no one way to be raped, there is no one way to survive a rape, there is no one way to report a rape and what that looks like — 10 minutes later, 10 months later or 10 years later,” Turkos said. “We are all doing our best.”