One of Jeffrey Epstein’s guards the night he hanged himself in his federal jail cell wasn’t a regular correctional officer, according to a person familiar with the detention center, which is now under scrutiny for what Attorney General William Barr on Monday called “serious irregularities.”

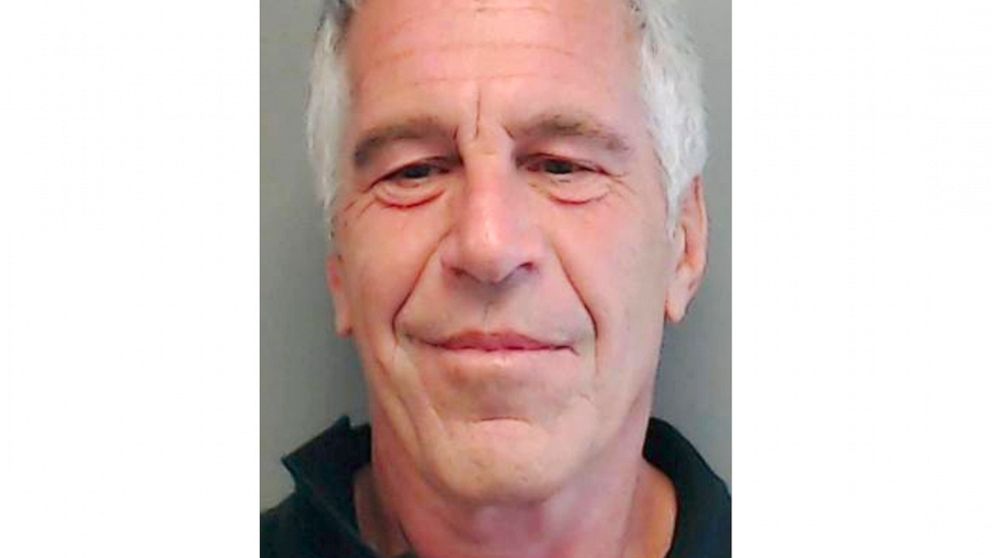

Epstein, 66, was found Saturday morning in his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, a jail previously renowned for its ability to hold notorious prisoners under extremely tight security.

“I was appalled, and indeed the whole department was, and frankly angry to learn of the MCC’s failure to adequately secure this prisoner,” Barr said at a police conference in New Orleans. “We are now learning of serious irregularities at this facility that are deeply concerning and demand a thorough investigation. The FBI and the office of inspector general are doing just that.”

He added: “We will get to the bottom of what happened and there will be accountability.”

In the days since Epstein’s death while awaiting charges that he sexually abused underage girls, a portrait has begun to emerge of Manhattan’s federal detention center as a chronically understaffed facility that possibly made a series of missteps in handling its most high-profile inmate.

Epstein had been placed on suicide watch after he was found in his cell a little over two weeks ago with bruises on his neck. But he had been taken off that watch at the end of July and returned to the jail’s special housing unit.

There, Epstein was supposed to have been checked on by a guard about every 30 minutes. But investigators have learned those checks weren’t done for several hours before Epstein was found unresponsive, according to a person familiar with the episode. That person was not authorized to discuss the matter publicly and also spoke on condition of anonymity.

A second person familiar with operations at the jail said one of the two people guarding Epstein in the hours before he was found with a bedsheet around his neck wasn’t a correctional officer, but a fill-in who had been pressed into service because of staffing shortfalls. That person also wasn’t authorized to disclose information about the investigation and spoke on condition of anonymity.

It wasn’t clear what the substitute’s regular job was, but federal prisons facing shortages of fully trained guards have resorted to having other types of support staff fill in for correctional officers, including clerical workers and teachers.

The news that one of Epstein’s guards wasn’t a correctional officer was first reported by The New York Times.

The manner in which Epstein killed himself has not been announced publicly by government officials. An autopsy was performed Sunday, but New York City Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Barbara Sampson said investigators were awaiting further information. A private pathologist, Dr. Michael Baden, observed the autopsy at the request of Epstein’s lawyers.

The Associated Press does not typically report on details of suicide, but has made an exception because Epstein’s cause of death is pertinent to the ongoing investigations.

The House Judiciary Committee demanded answers from the Bureau of Prisons about Epstein’s death. Committee chairman Jerrold Nadler, a Democrat, and the panel’s top Republican, Georgia Rep. Doug Collins, wrote the bureau’s acting director Monday with several questions about the conditions in the prison, including details on the bureau’s suicide prevention program.

Inmates on suicide watch in federal jails are subjected to 24 hours per day of “direct, continuous observation,” according to U.S. Bureau of Prisons policy. They are also issued tear-resistant clothing to thwart attempts to fashion nooses and are placed in cells that are stripped of furniture or fixtures they could use to kill themselves.

Those watches, though, generally last only 72 hours before someone is either moved into a medical facility or put back into less intensive monitoring.

The jail does have a video surveillance system, but federal standards don’t allow the use of cameras to monitor areas where prisoners are likely to be undressed unless those cameras are monitored only by staff members of the same gender as the inmates. As a practical matter, that means most federal jails nationwide focus cameras on common areas, rather than cell bunks.

Lindsay Hayes, a nationally recognized expert on suicide prevention behind bars, said that cameras are often ineffective because they require a staff member to be dedicated full time to monitoring the video feed 24 hours a day.

“It only takes three to five minutes for someone to hang themselves,” said Hayes, a project director for the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives. “If no one is watching the screen, then the camera is useless. There are a lot of suicides that just end up being recorded.”

On the morning of Epstein’s apparent suicide, guards on his unit were working overtime shifts to make up for staffing shortages, one person familiar with the matter said. The person said one guard was working a fifth straight day of overtime and another was working mandatory overtime.

Epstein’s death cut short a prosecution that could have pulled back the curtain on his activities and his connections to celebrities and presidents, though Barr vowed Monday that the case will continue “against anyone who was complicit with Epstein.”

“Any co-conspirators should not rest easy. The victims deserve justice and they will get it,” he said.

According to police reports obtained by the AP, investigators believed Epstein had a team of recruiters and employees who lined up underage girls for him.

ABC News aired video Monday of FBI agents and police arriving by boat at a private island in the U.S. Virgin Islands where Epstein had an estate.

In a court filing Monday, Epstein’s accusers said that an agreement he negotiated with federal prosecutors in Florida over a decade ago to grant immunity to his possible accomplices should be thrown out now that he is dead. Under that 2008 agreement, Epstein pleaded guilty to prostitution-related state charges and served 13 months behind bars.

At the time of his death, Epstein was being held without bail and faced up to 45 years in prison on federal sex trafficking and conspiracy charges unsealed last month.

Epstein’s death is the latest black eye for the Bureau of Prisons, which was already was under fire over the October beating death of Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger at a federal prison in West Virginia. The bureau is part of the Justice Department and falls under the attorney general’s supervision.

Taken together, the two deaths underscore “serious issues surrounding a lack of leadership” within the bureau, said Cameron Lindsay, a former warden who ran three federal lockups, including the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn.

A defense attorney for Epstein, Marc Fernich, also faulted jail officials, saying they “recklessly put Mr. Epstein in harm’s way” and failed to protect him.

Staffing shortages worsened by a partial government shutdown prompted inmates at the New York City jail to stage a hunger strike in January after they were denied family and lawyer visits.

Eight months later, the jail remains so short-staffed that the Bureau of Prisons is offering guards a $10,000 bonus to transfer there from other federal lockups.

In the wake of Epstein’s suicide, union president Eric Young of the American Federation of Government Employees Council of Prison Locals said a Trump administration hiring freeze at the Bureau of Prisons has led to thousands of vacancies and created “dangerous conditions” for prison workers and inmates.

In a statement, Young said that teachers, clerical workers and other support staff are regularly used to fill in for guards, and many guards are regularly forced to work 70- and 80-hour weeks.

Suicide has long been the leading cause of death in U.S. jails overall. In the federal system, suicides are rarer. At least 124 inmates killed themselves while in federal custody between fiscal years 2010 and 2016, according to the most recent statistics available from the Bureau of Prisons.

———

This story has been corrected to show that O.J. Simpson’s murder trial was in 1995, not 1994.

———

Sisak reported from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and Balsamo from Savannah, Georgia. Associated Press writers Curt Anderson, Michael Biesecker, Jennifer Peltz, David Klepper and Larry Neumeister contributed to this report.