The two brothers of the Stayner family are both famous, both tied to the wonder of Yosemite National Park, and both knew unspeakable horror.

Steven Stayner captured the heart of a nation when he helped another child escape from a pedophile, after enduring years of abuse and not wanting to see the child experience the same fate. Cary Stayner will forever be known for marring Yosemite’s reputation as a peaceful retreat with the brutal murders of four innocent women.

The Stayner family, made up of the two brothers, their three sisters and parents Kay and Delbert, lived in the secluded farming town of Merced, California, surrounded by almond groves and peach orchards, in the shadow of Yosemite National Park.

Watch the full story on “20/20” FRIDAY, Jan. 25 at 10 p.m. ET on ABC

“They call [Merced] the gateway to Yosemite,” said Ted Rowlands, a former reporter who covered Cary Stayner’s story at KNTV for the San Francisco Bay area.

Cary looked out for Steven, according to Cary Stayner’s former classmate Jack Bungart. “He loved his brother. You know, hung out with him, played with him.”

Martin Purdy, a friend of the brothers, remembered Cary as a “nice guy.”

“He was kind of a quiet guy. Our days would be– just get on our bikes in the morning and go to the park. Hang out with friends or skateboard,” Purdy told ABC News.

The boys were still in elementary school when a man named Kenneth Parnell entered the picture.

Parnell worked at the Yosemite Lodge, located about two hours away from the Stayner home. He befriended a co-worker named Ervin Murphy to assist him in a vile act that would shake the family forever.

“It was a sleety, wintery day,” Sean Flynn, a journalist who wrote about both Stayner brothers for Esquire, said. “He and Ervin Murphy got into Ken’s big, white Buick and drove into Merced.”

It was Dec. 4, 1972. Then-7-year-old Steven Stayner was walking home from school on Highway 140 when Parnell and Murphy were driving towards town. Stayner was lured into the vehicle and abducted.

“Kenneth Parnell stops the car and goes to a payphone, he comes back and tells Steven, ‘Your parents, I just spoke to them. They no longer want you,'” investigative journalist Pat LaLama said.

When Steven didn’t make it home from school, his parents sounded the alarm.

“Merced was the lead police department, and so they really mounted a large effort to search. And they searched. And there was just nothing there,” said Pat Lunney, an investigator assigned to Steven Stayner’s case.

“Cary was very upset,” childhood friend Mike Marchese told ABC News in a 1999 interview. “I heard stories about him going out and wishing on a star, that his brother would come home.”

For years, Parnell traveled around California with Steven.

“Steven Stayner had a new father figure, and it was Kenneth Parnell — who by day, was his father, and by night, was his rapist,” Rowlands said.

Steven was told his new name was Dennis Parnell and was enrolled in school. Against the odds, he flourished there.

“He had a great personality,” said Lori Duke, who dated Steven in high school but knew him as Dennis. “He was spunky. You could see that he wanted to play and be with kids and be normal.”

While Steven was a freshman at Mendocino High School, some 300 miles to the south, his older brother Cary was an upperclassman at Merced High School.

There was a “pall over” Cary, because he was “the kid who had his brother kidnapped,” said Bungart.

Cary Stayner “was a very, very good cartoonist,” and was voted “most creative” at school, according to Purdy.

Purdy said Cary Stayner always wore a hat. According to Rowlands, “He was wearing a hat because he was compulsively pulling his hair out. Emotionally, Cary Stayner had a tough time during his childhood.”

But Cary Stayner also exhibited some behaviors that made others uncomfortable, including, as he later admitted, exposing himself to his sister’s friend.

“It seemed as though he had a compulsion with trying to get close to women or be sexual with them,” Rowlands said. “But he was unable to develop any sort of interpersonal relationships with any women.”

The contrast between the two brothers is “surreal,” Flynn said.

“You have one brother who’s been subjected to just unspeakable horror for years, but by all appearances he’s a happy-go-lucky, jovial kid with a girlfriend. You have the other brother who’s left at home. Had no interest in girls, had no interest in people. And it wasn’t that he was just a loner, he was a bit of a creepy loner,” Flynn said.

By the time Steven was 14, he had been abused and manipulated by Parnell for seven years.

“At some point, Parnell and Steven together realized that Steven was growing up and that he was no longer going to be controlled by Parnell,” Lunney said. “Parnell wanted another kid that he could sexually assault.”

In February 1980, Parnell decided to capture a new, younger boy.

“He paid a local kid … to ride with him to the little town of Ukiah, California, puts this high school kid out on the street to go find him a boy, and he finds 5-year-old Timothy White walking home from school,” Flynn said.

For two weeks, Steven watched Timothy suffer the separation from his family. Then he took matters into his own hands. His high school girlfriend said he later told her what happened.

“He literally said, ‘I was not going to let that child go through what I had already been through. And if I didn’t take care of it now, it would just get worse,'” Duke said.

On March 1, 1980, Steven waited until Parnell was at work and then fled with Timothy. The two hitchhiked to Ukiah, California.

“It’s dark and Timmy can’t remember where he lives. So, Steven figures the best thing to do is to take him to the police station,” Flynn said.

Not only was Steven able to explain to police what happened to him and Timothy, he was also able to tell them his real name was Steven, not Dennis. Telling police, “I know my first name is Steven” became the most iconic moment in Steven’s remarkable story – later becoming the title of the book and a television movie.

“Steven was a national hero. He returns to Merced triumphant. Within days, he’s on ‘Good Morning America,'” Flynn said.

On GMA in March 1980, Steven shared with former host David Hartman that it felt “great” to be home. He told Hartman that his parents “didn’t change that much,” but his brother and sisters, “they changed a lot. I never recognized either one of them.”

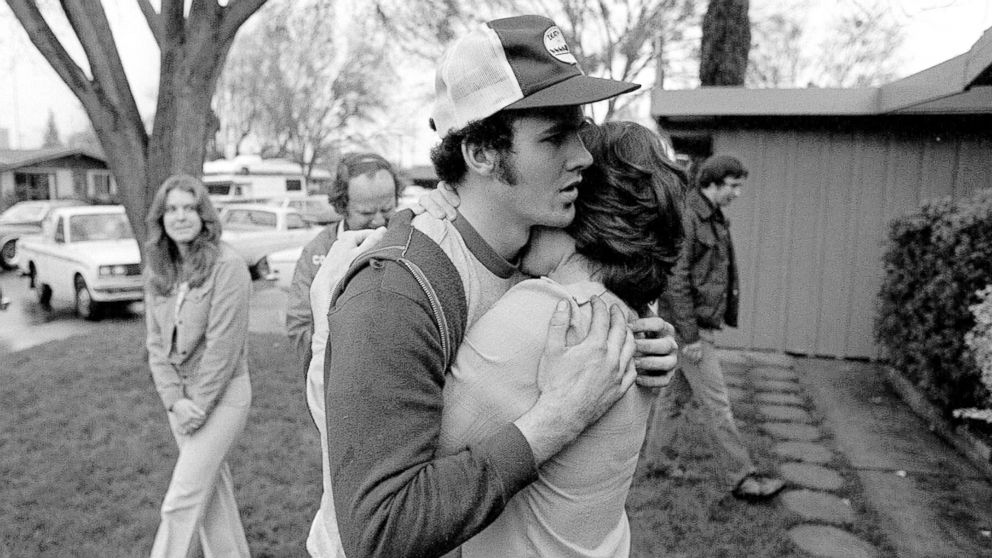

At a press conference outside the Stayner house, “everyone was smiling, there was a lot of jubilation, but if you look in the background, there’s something worth noting, and it’s Cary in his baseball cap, and he’s not smiling at all,” according to Flynn.

“Cary, as the older brother, had a very strange relationship now with his younger brother, Steven, who was getting all of this attention and who was a different person,” Rowlands said.

The brothers, four years apart in age, shared a room, but didn’t get along, according to Rowlands. “Steven didn’t understand the rules that he was now expected to live by.”

“The first year was kinda hectic,” Steven said on GMA in 1983. “For seven years I have been supposedly an only child. Now I had to compete with a brother and three sisters.”

Steven also struggled in high school where he was bullied for the tragic abuse he had endured. Flynn said his sexuality was “constantly under attack.”

In addition to his fraught life at home and at school, Steven, still just a teenager by this point, also had to face Parnell in court.

Parnell was convicted on kidnapping and false imprisonment charges. He was sentenced to seven years in prison but only served five — less time than he held Steven captive.

“It was outrageous. There was out and out fury over the sentence,” Flynn said. “Ken Parnell went back to what he had been doing for years. He found someone else to help him find another boy, only this time he was caught and he was sent to prison again — where he died in 2008.”

While Steven was grappling with life after his escape, his brother was out of high school with his own troubles.

“I think Cary after high school seemed a little lost, like he didn’t know where he was going,” Bungart said.

He was known to take refuge in nearby Yosemite, where he’d drive up and get lost in nature.

“Whatever demons were clamoring around in his head, by being naked, by smoking pot, he could find the peace that he so desperately needed,” LaLama said.

Steven Stayner’s fame was short-lived. He grew up, got married and had two kids.

“He was very proud of who he was,” his wife, Jodi Stayner, said in 1999. “He was just very well grounded, for a person that had gone through what he had gone through.”

Tragically, Steven Stayner was killed in a 1989 motorcycle accident at age 24.

Shortly after Steven’s death, an uncle with whom Cary Stayner was very close was shot and killed in a home they shared together. By this point, Cary Stayner was suffering. Flynn said Satyner had “a couple of nervous breakdowns,” one of which was “fairly violent.”

“He stated that he felt like jumping in a truck, driving it through the shop and killing the boss and killing everybody in the office, and then torching the place,” friend Mark Marchese said in 1999. “That’s when I told him, ‘You need to go to a doctor, Cary.'”

But instead of seeking mental health treatment, Stayner “ended up taking refuge” in Yosemite, Rowlands said.

In 1997, Stayner got a job as a handyman at the Cedar Lodge, seven miles from the gate of the national park.

“Working at Cedar Lodge gave Cary access to his beloved Yosemite,” Rowlands said. “His idea of serenity was to maybe smoke a little pot and to sunbathe naked.”

Stayner had been at Cedar Lodge for two years when Carole Sund, her teenage daughter Juli Sund and her friend Silvina Pelosso came to stay one night in February 1999. That night, he talked his way into their room under the guise of fixing a leak, and then sexually assaulted both girls and brutally murdered all three.

Jeff Rinek, at the time an FBI agent handling Cary Stayner’s case, said the search for the women was the “largest… ever mounted in Yosemite at any time.” After several weeks, the bodies of all three women were discovered.

Five months passed without another killing, and the community surrounding Yosemite was lulled into a sense of calm – especially when the FBI announced that those they believed responsible for the murders were in custody. In fact, the wrong men were custody.

On July 21, 1999, when Stayner saw Joie Armstrong, a 26-year-old naturalist at Yosemite who taught children about nature in the park, “something instantly” changed with him, Rowlands said. “He’s ready to kill again.

After her friends reported her missing, police found signs of a struggle at her cabin and half a mile away, they found her body. Her head, which had been removed, was found several feet away in the water.

“There wasn’t really much time for us to speculate on whether this was related, I mean it quickly became related,” said Des Kidd, former medical director at Yosemite who participated in search and rescue.

Stayner left a substantial amount of evidence in and around Armstrong’s cottage, but police initially started searching for him because his vehicle had been seen near her place and they thought he would be a “natural witness to interview,” Rinek said. Authorities had already interviewed him once before about the other three murders, but at the time he hadn’t raised any red flags.

FBI agents caught up with Stayner at a nudist colony, where he had fled to after Armstrong’s murder. After he was brought in for questioning, he confessed to murdering Joie Armstrong, describing the brutal killing “as if he was reading a soup label,” said John Boles, another FBI agent on the case.

Soon after, he confessed to murdering Carole Sund, Juli Sund and Silvina Pelosso.

“I went to ask if Cary wanted to talk. He said, ‘I want you to get a hold of some producers in Los Angeles. I want a movie-of-the-week made about my story,'” Rowlands said. “There was a movie made about Steven Stayner. And he wanted the same treatment. He wanted the world to take note.”

“It’s difficult for me to picture what Cary has done and knowing Steve because their personalities are completely opposite,” Duke, Steven’s former girlfriend, said. “The only time Steve would kill anything like a fish is because we were gonna eat it. You know what I mean? … I wouldn’t think that he would think of himself as one, but he is a hero.”

For the last 20 years, Stayner has been on death row at San Quentin prison. He’s 57 years old.

“As far as I know, he’s never talked to anyone about the effect Steven might have had on his crimes. I’m not sure there is any direct cause and effect,” Flynn said. “Steven could have grown up normal happy and healthy and Cary still would’ve been a serial killer.”