The discovery of the body of Hania Noelia Aguilar, a 13-year-old girl who was raped and murdered after being kidnapped outside her home, broke hearts in the small community of Lumberton, North Carolina, last fall.

But the discovery that the man suspected of killing her was linked to another rape and could have been detained at least a year earlier generated a whole different emotion: anger.

“It is absolutely tragic and makes me sad and a little bit crazy that this girl was killed, and if the case had been investigated properly, chances are she would be alive today,” North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein told ABC News.

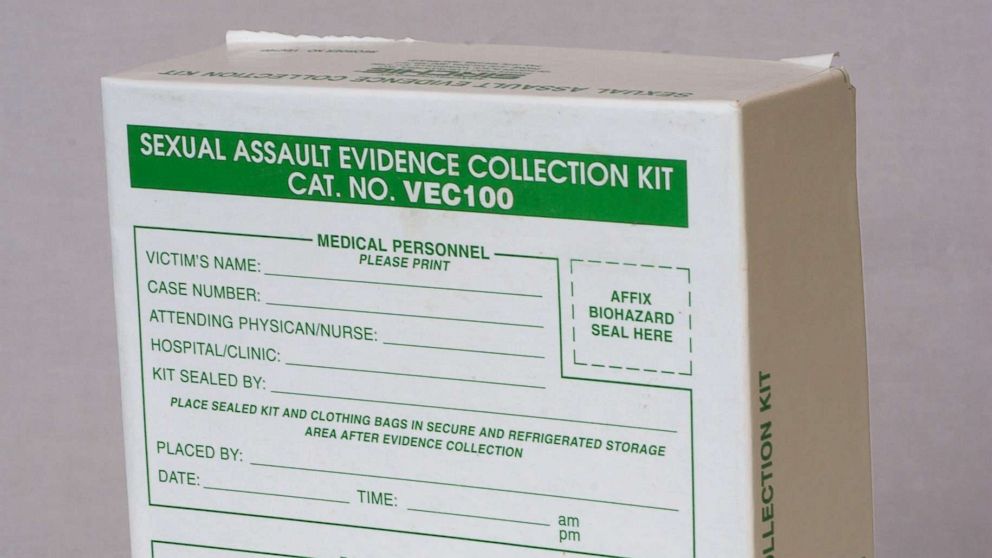

Last week, the Robeson County Sheriff’s Office fired an investigator after an internal probe found that Aguilar’s suspected killer could have been detained before she was abducted — DNA evidence from a rape kit linked the suspect to a 2016 rape case, giving the sheriff’s office probable cause to seek a search warrant.

The rape kit evidence linked to Aguilar’s suspected murderer was collected in 2016 and tested in 2017, but ultimately — for publicly unknown reasons — law enforcement did not follow up on it.

“If he had been linked in 2016, we’d be having a very different conversation,” Monika Johnson Hostler, executive director of the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault, told ABC News.

The fact that the 2016 rape kit had been tested at all is remarkable, critics say. Between 14,000 to 15,000 other rape kits in North Carolina are waiting their turn in a massive backlog that’s been piling up for years, leaving potential repeat offenders like Aguilar’s alleged killer free to find their next target.

“Every single sexual assault kit that is untested represents a human being who went through an awful trauma, and they as a human being deserve to have their case investigated fully,” Stein said.

Testing rape kits can both help get justice for a survivor and stop a person from committing sexual assault or further offenses, according to Ilse Knecht, director of policy and advocacy at the Joyful Heart Foundation, a national organization tackling sexual assault. Because of that, a rape kit backlog “is a public safety issue,” she said.

“These are preventable crimes in many ways,” Knecht told ABC News. “We have the technology, we have the science, to take these very, very dangerous people off the streets, and it hasn’t been used.”

North Carolina has the highest known number of untested kits of any state, according to data collected by End the Backlog, a Joyful Heart Foundation initiative. Knecht estimates it will take “years and years” to test them all. The next highest state is California with 13,615 untested kits — and four times as many people.

North Carolina has been taking steps to eliminate its backlog.

Last March, a North Carolina Department of Justice report found over 15,000 rape kits remained untested at the end of 2017.

In October, North Carolina received a $2 million grant from the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, about half of which will be used to train law enforcement in victim-centered and trauma-informed investigations.

About $1 million — the highest amount allowed under the grant agreement — will be used to outsource rape kit testing to private labs (which is faster than public labs). However, that amount of money can only test about 1,400 kits — around 10 percent of the backlog.

Still, it is “kind of a pilot for us to see exactly how this process is going to go for us,” Hostler said.

The grant is also going towards implementing a tracking system, putting a barcode on each kit so the state knows the number and location of kits. Survivors will have access to track their kits, so they’ll know its status and “where to apply the pressure,” Stein said.

When a rape kit is tested, DNA information is submitted to the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, to see if there is a match to a person with a past offense and to identify serial offenders.

So far, Stein told ABC News, about 10 percent of tested kits link to someone on the CODIS list. Stein expects that percentage to increase the more testing is done as the database will grow.

And there have been significant results in the state, even before the grant was obtained. In Fayetteville, after a kit was tested, police charged a suspect in June over a 1989 rape case that had gone cold, ABC affiliate WTVD reported.

In Greenville, where police committed to testing their backlog, of the 21 cases uploaded into CODIS, two offenders were identified as serial rapists, reported CBS affiliate WNCT.

Law enforcement has had “a growing recognition that this is something where we need to change the way it’s been done in the past [and put] a greater emphasis, a greater prioritization on addressing these crimes,” Stein said.

But more funding is needed to get through the rest of the backlog.

Last year, state lawmakers showed “bipartisan support, but the funding didn’t show up,” Hostler told ABC News.

“Funding’s always far more difficult than verbal support, so I’m hoping that the verbal support will turn into more funding this year,” she added.

Stein told ABC News he will be appealing for funding to the state legislature again when it is back in session in early February after they did not give it last year.

He said he will announce a proposal including a request for funding to outsource kit testing as well as “to establish a state protocol that says any time you collect a sexual assault kit and the victim reports it to law enforcement, as a matter of protocol, you just send it to the state crime lab. Don’t hold it on your shelves, don’t wait. Just send it to us so that we can analyze it and see if this sample hits on the CODIS database.”

But it’s about more than just testing, Knecht said.

“You have the cases coming back that need to be investigated, they need to be prosecuted aggressively, and then all the victims in those cases need to be reengaged with the system that let them down,” she said.

Stein echoed that from a justice perspective, rape kits and CODIS are “only as effective as we in law enforcement are at utilizing the information.”

The Aguilar case put that reality front and center.

Before that case, Stein had been working on a letter that will go out to local law enforcement when a CODIS hit is found telling them the State Bureau of Investigation has offered to pursue investigations for any agency that doesn’t have the resources to do so.

First, however, the kits need to be tested.

“If more people understand … the public safety threat, there would be a much larger chorus of voices saying, ‘Test these kits now,'” Knecht said.