This week on “The Bachelor,” contestant Caelynn Miller-Keyes told Colton Underwood that she was drugged and raped four years ago while she was in college.

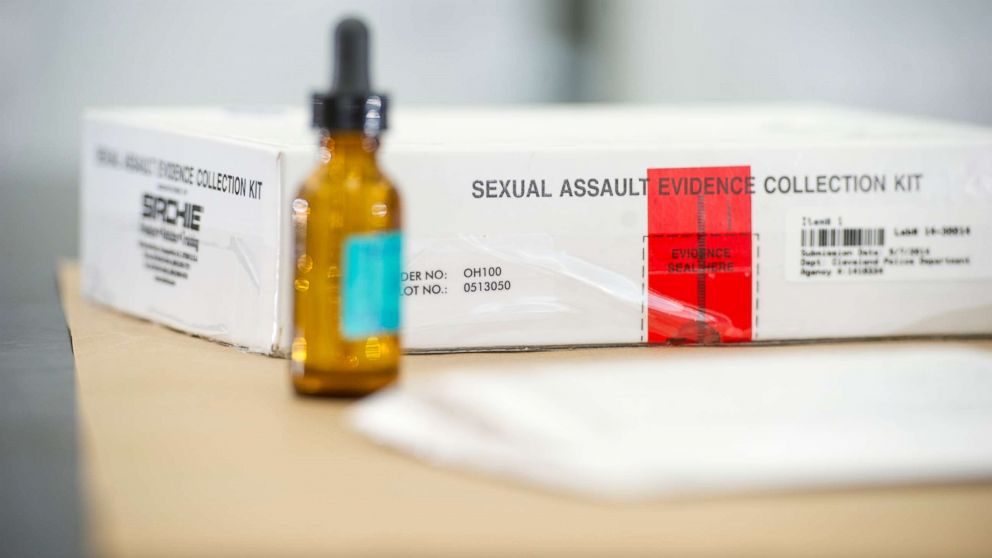

The 23-year-old Virginia Commonwealth University graduate said she went to a hospital to have a rape kit performed the morning after the alleged assault, but “they told me they wouldn’t do a rape kit unless I filed a police report.”

Eventually, she was able to get a rape kit collected at another hospital, but because so much time had gone by since the assault, “the results were inconclusive,” she said.

But advocates say Miller-Keyes should never have had that experience — and are trying to help other survivors know their rights. Nurse experts say a police report is not required to have a rape kit administered; a survivor does not have to decide whether they intend to file a report to have evidence collected in this way.

“No hospital emergency room should turn a sexual assault patient away who is seeking care,” Jennifer Pierce-Weeks, the CEO of the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN) told ABC News. A joint position statement from the IAFN and Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) issued in 2016 echoes this.

Patricia Kunz Howard, president of the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA), agreed.

“At my facility, we obviously would do an exam and would contact the police, but their choice whether or not to make a report is their choice,” Kunz Howard told ABC News. “We can’t force them to make a report, but we’re not going to deny anyone safe, compassionate, victim-centered care.”

Both IAFN and ENA issued a joint position statement on the issue in 2016. And the Violence Against Women Act actually requires that states provide rape kits for free in order to qualify for anti-crime grant funding, according the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN).

Additionally, the Sexual Assault Survivors’ Rights Act, which was signed by President Obama in 2016, stipulates that a survivor has the “right not to be prevented from, or charged for, receiving a medical forensic examination.”

However, sexual assault cases are often handled on the state level, and not all states have passed their versions of the federal survivors’ rights act. According to Rise, a civil rights nonprofit supporting the act, 14 states passed the Survivors’ Bill of Rights. A version of the bill was signed by then-Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe in 2017 — the year Miller-Keyes graduated, according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

In Virginia, survivors can have a rape kit examination performed anonymously, according to Sara Jennings, the manager for Bon Secours Richmond Forensic Nursing Services and IANF’s president.

“If you’re 18 or older and you’re a victim of either sexual violence or domestic violence, that’s not mandated to be reported to law enforcement,” Jennings told ABC News. “So there are options for a patient to have what we call a ‘blind’ or anonymous physical recovery kit (or what is commonly referred to as the rape kit). So they can come to the hospital, not have any contact with police, and still have that evidence collected if they were to change their minds at a later time.”

But just because there are laws in place to protect survivors who do not want to file a police report doesn’t mean they’re followed. Bon Secours, a full-service clinical forensic program in Richmond with 14 full-time forensic nurses, often gets calls from local health care providers unaware of the “blind” option, Jennings said.

The organization will walk providers through a survivor’s options in Virginia: to just get medical treatment, to get medical treatment and a kit without reporting the incident to police, or to get medical treatment and a kit and report the incident to law enforcement.

But it isn’t just Virginia. Nationwide, Pierce-Weeks said she has “consistently” seen cases that when a hospital doesn’t have a sexual assault nurse examiner program, it will sometimes turn survivors away, saying they can’t provide services, an issue also reported by Cosmopolitan in 2016.

Sexual assault nurse examiners, or SANEs, are registered nurses who go through training, practice and certification about caring for survivors of sexual assault. There are 1,545 certified SANEs in the U.S. as of the end of 2018, per IANF, but a higher number of nurses are practicing, and there has been a recent increase in nurses going through and requesting training.

“But are there enough? No,” Pierce-Weeks said. IANF estimates only 17 to 20 percent of hospitals have SANE services available.

Even without SANE services, though, the nurse associations’ leaders say hospitals should not turn survivors away, following best practices of medical care.

“Sexual assault victims should really be able to show up at any hospital emergency room and receive a minimum standard of care. That minimum standard of care does not have to be a SANE program or a sexual assault nurse examiner specifically,” Pierce-Weeks said.

A “minimum standard of care” doesn’t just include the option for evidence collection and rape kit administration, Pierce-Weeks explained. It also includes emergency contraception, HIV and STI prevention or screening and any other medical need the person has.

The path to justice for a sexual assault survivor requires a variety of factors going right across multiple systems, and one of the first steps is a hospital’s reaction, advocates say.

“We put a lot of onus on the survivor to know what to do and to have a plan if something like this were to happen. That simply is just not the right approach,” Pierce-Weeks said. “Having said that, one of the probably most effective things that a survivor can do is to call the sexual assault hotline and speak to an advocate in their own community.”

That community advocate can advise a survivor on where to go for care, like which nearby hospitals have SANE services, and can also provide long-term information about their rights.

“Best practice says that every sexual assault victim receive an appropriate exam with the correct evidence collection that protects it in a forensic manner and is focused on making sure that the victim is safe, has appropriate community support, their psychological well-being is taken care of, and their medical needs are met,” Howard said.

Miller-Keyes said she did not get that immediate, trauma-informed care. But her decision to use “The Bachelor,” and her platform as Miss North Carolina USA to speak about sexual assault is a way to help others know their rights.

“If you watch ‘SVU’ on television, it looks so easy, but it’s not,” Miller-Keyes said on “The Bachelor.” “It takes time, and it takes a lot of no’s, and hopefully eventually you can get justice.”