Experts have long acclaimed the benefits of prisoner animal programs for both the inmates and dogs, but sometimes the journeys end in even more of a fairytale than anyone could have been imagined.

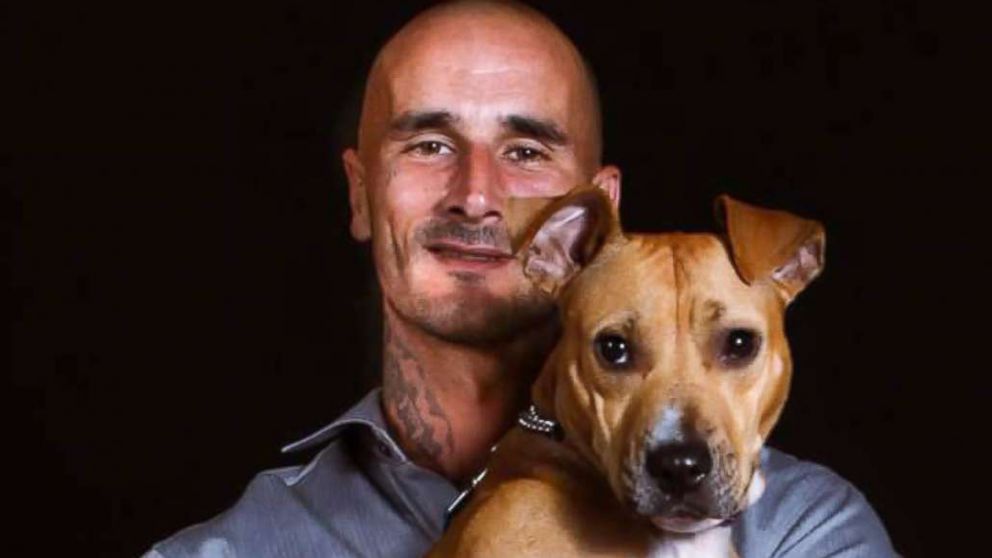

Former inmate Jason Bertrand, 36, participated in the Florida Department of Corrections-approved TAILS program, which stands for Teaching Animals and Inmates Life Skills. During his time there, he developed such a bond with his assigned dog, a pit bull mix named Sugar Mama, that the program and facility he was being housed in allowed him to adopt her after she graduated — even though he still had months left in his term.

Sugar Mama, who is now about 4 or 5 years old, altered Bertrand’s outlook on life and allowed him to stay out of prison, he told ABC News.

Bertrand is a prime example of the program’s ability to assimilate inmates back into society while also rehabilitating and finding homes for hard-to-adopt dogs, said Jen Deane, executive director of TAILS and Pit Sisters, a Jacksonville-based organization that takes dogs in need from city shelters, in an interview with ABC News.

Bertrand had a rough childhood that he says set the stage for a life of crime. His father, a heroin addict, has been in and out of jail since he was 10, and his mother, who was 15 when she had him, abandoned him when he was a kid, he said.

When Bertrand was 16, he was charged with felony battery for breaking another kid’s jaw, he said. He was adjudicated as an adult and spent nearly two years in prison, according to the Florida Department of Corrections’ online records.

When he was released at 19 years old in August 2001, he went to live with his father, who was still addicted to heroin, he said. His father, however, was soon evicted from his home, and Bertrand — and his sister — had to find a new place to live. Bertrand told ABC News that at the time, he wasn’t prepared for the responsibilities of providing for a household.

“I couldn’t pay the bills,” he said. “I had no sense of direction. I didn’t know what to do. My father did crime his whole life. I just figured I’d go rob a few things.”

Less than five months out of prison, Bertrand committed five burglaries between Dec. 24, 2001, and Dec. 27, 2001. He used a BB gun, which earned him five charges of robbery with a deadly weapon, his criminal records show.

While Bertrand readily admits wrongdoing in the crime spree, he said he was just trying to put a roof over his and his sister’s heads.

But Bertrand had already committed a felony in the past. This triggered Florida’s prison release re-offender law, which commanded a mandatory minimum of 30 years for each first-degree felony charge, he said. A plea deal allowed him to instead serve a mandatory minimum sentence of 15 years for five second-degree felonies concurrently, he said.

Bertrand was on the tail end of his 15-year sentence when he discovered the program that would forever alter the course of his life.

In 2016, Bertrand was being housed at the Jacksonville Bridge Community Release Center, a halfway house managed by the Florida DOC, when he joined the program. At first, he did it for “selfish reasons.”

Getting accepted into the program, which vets both the inmates and dogs before it starts, was a step above on the quality of living “hierarchy” in the facility, he said. While other inmates complained of the dog smell, Bertrand saw it as an opportunity to break up the monotony of his prison sentence. He went into it unaware of the benefits of participating in the program.

“It was kind of one of them things — when you get into something, you get a big surprise that you weren’t expecting,” he said. “Sugar Mama was my big surprise.”

“Who doesn’t want to have a dog when you’ve been incarcerated forever?” he added.

He started as a floater and would help around as needed, since there weren’t enough dogs to go around, he said. Sugar Mama, a tan pit bull mix weighing about 40 pounds, had been seized from a dog-fighting environment in Palatka, Florida, that left her back broken in three places, Deane said. She entered the program late and had just had surgery when she would meet her future owner.

The two had an “instant bond,” Deane said.

“I couldn’t imagine somebody doing something to her like that,” Bertrand said, adding that she was still “sweet” and “rambunctious” despite being so hurt that she had to be carried everywhere at first.

For 15 years, Bertrand lived in “a different world” that doesn’t allow for “basic” human needs such as displaying emotions or giving a hug for fear that it could be misconstrued as weakness.

The emergence of Sugar Mama in his life changed that.

“I was able to hug her, pet her,” he said. “When I took her on walks, I could talk to her.”

Bertrand threw himself into his work while participating in the program, saying that he was “trying to be positive” and “do things that were above and beyond.”

Deane noticed his work ethic as well, saying Sugar Mama seemed to be his “reason for being.”

For the first time, he was responsible for another living thing after a lifetime of having the attitude of “F— everyone else,” he said. He didn’t allow himself to think that way for fear of getting kicked out of the program, he said.

Being concerned for a living thing other than himself surprised Bertrand.

“Sugar Mama, for me, was my introduction to what it meant to be human,” he said.

The rescue pup also taught him patience and how to communicate effectively.

“When she was crazy because she was raised in a bad environment, such as myself, I had to communicate with her in a way that she could understand,” he said. “I couldn’t yank her to the side when she pissed me off.”

He added, “In prison, that’s what you do… Somebody will punch you and take everything you own. You learn to be aggressive back.”

When it came to graduation time, Bertrand couldn’t bear the thought of parting with the sweet dog he had grown to love. Sugar Mama was set to graduate about four or five months before Bertrand was done serving his sentence in December 2016, so he begged Deane and his supervisors at the facility to let him keep her.

Deane recalled Bertrand coming to her in tears.

“He said, ‘Miss Jen, I need to have this dog. She is my life. I will live under a bridge if that means keeping my dog.'”

After Deane spoke with the director of the halfway house, they decided together that it was in the best interest of both the inmate and the dog to stay together.

“They made an exception to let her live there until he was released,” Deane said. “The day he left, she left, and we were there to see her go.”

Bertrand said that after getting to know Sugar Mama, he saw his old self in her abuser and “wanted to change.” The TAILS program was essential in that revelation, and others saw the positive change in him as well, he said.

“Prisons just release you back into society,” he said. “Work release programs just give people money. Money doesn’t mean success. Money just means you have money.”

In Florida, 24.5 percent of inmates who were released in 2014 returned to prison within three years, according to a Florida Department of Corrections report released last year. Bertrand, however, doesn’t see himself returning to prison because Sugar Mama wouldn’t be taken care of, he said.

Having Sugar Mama in his life has led to a snowball of successes for Bertrand.

“I got out of prison, I met my wife, I had other reasons to stay out of prison,” he said.

Now, Bertrand works full-time as an air conditioner installer in Dunedin, Florida. He said his work fulfills him and his decent hourly wage allows him to put his wife, Crystal Bertrand, through dentistry school full-time.

“I’m really good at my job,” he said, adding that he relishes in the stability that his family, which also now includes a 13-year-old Jack Russel terrier named Emma, brings him.

Deane and Bertrand have struck up a kinship after the program. Deane describes Bertrand as an “amazing man” and “one of the nicest guys you’ll ever meet,” and Bertrand considers Deane a “good friend.”

Bertrand also drives to Jacksonville once every three months to give motivational speeches to inmates, Deane said, describing him as “very gifted” at doing so.

“He commands a room like nobody else,” she said. “So, I’m very lucky to be working with him.”

Sugar Mama, meanwhile, has settled into her role as the “princess” of the house, Bertrand said. She’s so spoiled that when she jumps on the couch, she won’t sit down until someone puts a blanket down for her, he added.

Bertrand said adopting Sugar Mama is “what regular convicted criminals lack on their release,” calling her “the beginning” of his new life.

“You spend your whole life really amounting to nothing, and all of a sudden, things are going good,” he said. “It’s a really good feeling.”